James Britton noticed that poetic writing was often missing from school and undervalued. He defined poetic writing as “a language for not doing something, but for making something…”

Writing to learn

I work from a constructivist theory. Students explore, interview others, analyze mentor texts, invent, and draw conclusions about possible answers to questions we pose.

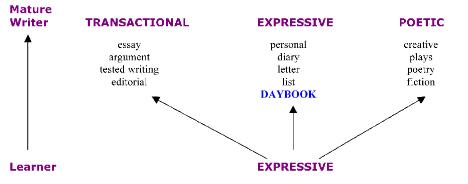

I draw inspiration from James Britton. He encourages writers to explore expressive writing (lists, diaries, notes, brainstorming – writing not intended to be shared). Writing expressively makes sense to me. From writing in a daybook and knowing that no one was looking over my shoulder, I found I liked to write and I had something to say. It is the stuff of which writing notebooks or daybooks are built.

Britton explains in his “Notes on a Working Hypothesis” written in 1979 that still rings true today. “Whether we write or speak expressive language is associated with a relationship of mutual trust, and is therefore a form of discourse that encourages us to take risks, to try out ideas we are not sure of, in a way we would not dare to do in, say, making a public speech. In other words, expressive language favors exploration, discovery learning (The National Writing Project Network Newsletter, Volume One, Number 3, by James Britton).

He noticed that poetic writing was often missing from school and undervalued. He defined poetic writing as “a language for not doing something, but for making something…”

He defined the third function of writing as transactional. We use this form when we want to do something. We employ transactional writing to persuade, to inform, and share information. Schools and the world value transactional writing highly because it is through transactional writing that things get accomplished.

In the Writing Project, teachers find that by designing writing assignments that take writers through writing expressively and poetically, we explore our subjects thoroughly. By writing about topics as brainstormed lists, poems, and plays, we discover and articulate what we want to do and what we want to say. In other words, transactional writing is easier for many of us if we explore the other functions of writing first.

For example, I asked a class of 6th graders to brainstorm a list of emotions. They chose one to write about. The students wrote 3-5 minutes about the topic. They analyzed the writing by underlining the key words. Students organized just the key words they had underlined into poems. After writing the poems, students were so ready to write a claim. From the expressive and poetic writing, they knew why they felt the way they did. They could write generalizations easily and were ready to write persuasively. Between each step, they conferred with a partner, sharing their lists, reading or paraphrasing their writing. The talking helped build the momentum as well and gave them permission to do what they love to do: talk with their friends!

Try the lesson above or try this one. Meet the students at the door and hand them this worksheet: “Choose something you feel strongly about. Persuade someone why you feel the way you do. Support your claim with evidence.” Which assignment will be met with more groans? From which will your students learn more? Thank you James Britton!

NEXT: Helping students find their topics